Rolling Stock

Who owns the trains? ROSCOs and repatriated profits

Britain’s ongoing industrial dispute between the RMT Union and train operating companies this summer has put the spotlight on railway assets. Alejandro Gonzalez reports

I

n the realm of British rail transportation, a curious financial arrangement defines the landscape of locomotives hurtling across England, Scotland, and Wales.

The vast majority of these trains, those that faithfully ferry passengers to their destinations, are not assets owned by the train operating companies (TOCs) that manage their daily journeys.

Instead, they belong to rolling stock companies (ROSCOs), entities that lease the engines and carriages to TOCs, all under government-issued franchises. An intriguing contrast emerges north of the border, where in Northern Ireland, the state-owned NI Railways stands as the custodian of the rails.

Privatisation

This ROSCO-leasing framework, a ‘hallmark’ of British rail privatisation, traces its roots to the Conservative government under Prime Minister John Major, who set in motion the privatisation of British Rail (BR) over three decades ago. In its implementation, BR underwent a dramatic three-way division:

- Rail infrastructure: The tracks and signalling, the very arteries of Britain’s rail network, were relinquished to private hands, initially through the sale to Railtrack, a consortium that would later evolve into Network Rail.

- Passenger transport provision: The business of catering to passengers’ travel needs was subjected to a franchise system. This public-facing facet of rail transport was tendered out to TOCs, distinct entities that presided over various regions. The catch: they operated with the assurance of public subsidies, contingent on a commitment to invest in enhancing the quality of service.

- Railway fleet: The railway vehicles, from age-old carriages to gleaming new locomotives, saw a different fate. They were bundled up and sold to the three ROSCOs: Angel Trains, Eversholt, and Porterbrook. These companies were tasked with managing these rolling stock and leasing them to the freshly minted franchisees.

Birth of ROSCOs

The financial implications of this transaction were substantial. In 1993, the BR passenger fleet, if assessed by approximate book value, stood at £2 billion, according to a June 2017 House of Commons briefing paper. However, the government’s proceeds from the sale of the ROSCOs exceeded this mark, reaching an impressive £2.5 billion, as stated at the time.

But here’s the twist – subsequent reports, notably those from the National Audit Office (NAO) and the Commons Public Accounts Committee in 1998, painted a different picture.

They contended that the sale of ROSCOs had been hastily executed, leading to a tangible loss of value for the taxpayer.

The NAO’s meticulous calculations revealed that had the ROSCOs’ future cash flows, under the continued umbrella of public ownership, been allowed to thrive, the value could have reached £2.9 billion.

In contrast, the government’s sale, including sale proceeds, transferred risks, and potential tax receipts, amounted to a more modest “up to £2.2 billion,” according to the House of Commons briefing paper.

Over the years, the ROSCOs have been no strangers to the highs and lows of the marketplace. In a series of buyouts and divestitures, Angel Trains, originally acquired for nearly £700 million in 1996, was later sold for a staggering £3.5 billion in 2015.

Eversholt, purchased for £518 million in 1996, found a buyer for £2.5 billion in 2015. Porterbrook, another 1996 acquisition at £528 million, was sold for an undisclosed sum in 2014.

See: Angel Trains up for sale, All change in wake of Angel Trains sale and HSBC is last bank to quit ROSCOs

In 2006, under the Labour government, an inquiry was launched by the Competition Commission into the practices of ROSCOs, examining allegations that they had been overcharging TOCs, claims rejected by the ROSCOs themselves. In its findings, the commission identified a lack of competition stemming from a shortage of available vehicles for lease.

See: Competition Commission blasts ROSCOs over train leasing costs and CC rules Roscos restrict choice

Mini-ROSCOs

Recent years have witnessed the emergence of competitors, often referred to as “mini-ROSCOs,” in the market. These specialist train leasing companies have begun to challenge the dominion of the major players. These include:

- Beacon Rail

- Caledonian Rail Leasing

- GE

- Halifax Asset Finance

- Rock Rail

- Akiem Group (bought Macquarie European Rail)

- Lombard North Central

Nevertheless, the big three ROSCOs continue to wield substantial influence, retaining their grip on approximately 87% of the existing rail network fleet, a fact underscored by the Rail Delivery Group in 2018. Transport experts assert that they preside over no less than 70% of the rolling stock that traverses the nation’s rail network.

Pandemic years

The advent of the COVID-19 pandemic introduced a fresh layer of complexity into the landscape. With the government’s pivotal role in the nation’s economy taking centre stage, public services found themselves in receipt of a substantial lifeline, amounting to a staggering £14 billion (with £3.5 billion towards rail services) in 2020.

On top of this, the UK government also provided around £15.85 billion to support 15 privately owned franchised operators from March 2020 to December 2022.

This financial injection was a response to the seismic shift in demand dynamics, driven by the emergence of the “work from home” norm. The government effectively stood as the guarantor, ensuring the train operators would honour their lease payments to the ROSCOs.

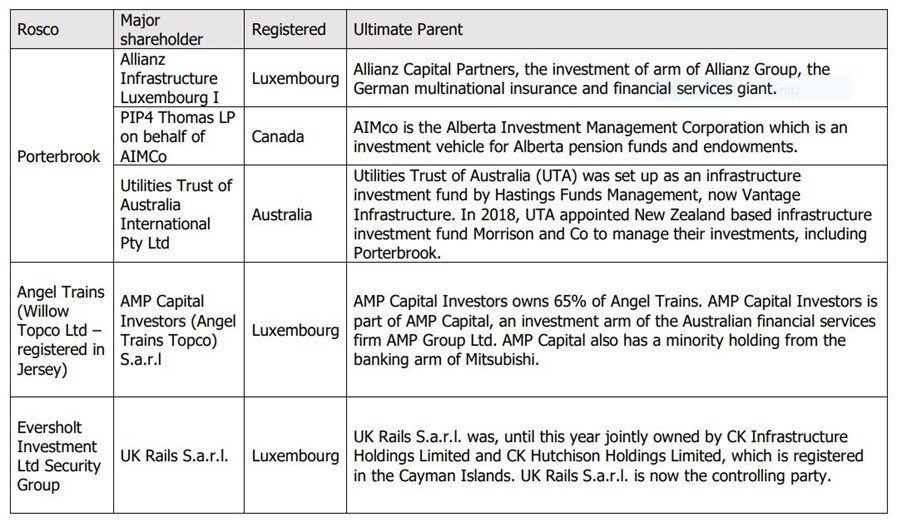

In an October 2021 report issued by the Rail, Maritime and Transport (RMT) workers’ union, an intriguing aspect of the ROSCOs’ financial arrangements came to light when it was disclosed that all three ROSCOs, those custodians of the railway assets, had parent companies ensconced in low-tax jurisdictions.

This revelation raised interesting questions about dividends.

“The rolling stock racket is a long-established scandal on the railways … in the last 10 years, the rolling stock companies have paid out £2.7bn in dividends to their owners. These dividends typically represent around 100% of their pre-tax profits. The average dividend payment is around £260m each year.

“On average this extraction of profit represents around 13% of what the Train Operating Companies – and now the government – pay to the rolling stock companies. It represents an average of 2.8% of total expenditure by Train Operating Companies,” according to the RMT.

In the financial year of 2020, a total of £950 million in dividends, RMT calculated, made their way into the hands of shareholders, with critics noting that the taxpayer was underwriting private profit-making endeavours, with little tangible return on investment for the public purse.

The ROSCOs’ overseas parent companies

Source: RMT Union

This complex financial arrangement underscores the evolving dynamics of railway finance, where taxpayer funds and offshore tax havens intersect, casting a spotlight on the question of where the public's investment truly finds its destination.